There is a project for the sun. The sun

Must bear no name, gold flourisher, but be

In the difficulty of what it is to be.

—Wallace Stevens, “Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction”

I.

Darkening and it grows late.

The rain comes cold and

slow. The wind is thick,

the blackbirds lilting. All

the wood is sound and

motion. Then a chestnut:

impressions of the thing,

appearances, dark limbs

against a grey Dutch sky.

II.

When ere I saw the chestnut first, I took

From that botanic garden as my own

The image of its form—for it had grown

There at the taxis of the bridge and brook.

Grey was its bark, and fissured; in the crook

Of branchtips palmates sprawling outwards shone

With greeny serrate leaves; therein were sown

White panicles, pink-tongued, fair upon to look.

As Adam out among the beasts, I assayed

To name and take this object of étude

And fix its roots in that syntax of clades.

Aesculus it was by essence, or by name,

For there it stands in the System construed

By Carolus, which makes universal claim.

III.

They were in Acre, that frayed

crusader stronghold, walking

down the alleys of the market,

the limestone slick with rain,

past the seacatch and the blue

tarps rattling in the wind.

The city smelled of brine

and smoke, and everything

was grim, except the copper

pans and bagatelles turning

slowly in the rafters. The seagulls

shrieked overhead, the air cold

and grey as the water. She

was hungry, so they ate

chestnuts from a paper sack

beside the Mandate-era prison.

They were dry, crumbly,

vaguely sweet; bits of shell

caught stiffly in his teeth.

“When we get to Haifa,” he said,

“Let’s spend just a night.”

IV.

“High in air,” writes Melville,

“the beautiful

and bountiful

horse-chestnuts,

candelabra-wise,

proffer the passer-by

their tapering

upright cones

of congregated blossoms.”

This is New Bedford,

whence the Pequod sallies forth,

bearing Ishmael & Ahab

out

to have that precious oil,

and Ahab on his hunt

for vengeance ‘gainst the whale

who had so maimed

& torn his leg asunder.

And on the way

seeks Ishmael to rectify

old, gross delusions

of the whale by mounting intimate

account of it, correcting

knowledge. He gives

the hoary histories,

the Bible

and before.

He tells the second hand

accounts, and discourses

on failings

of sophistricated portraits.

He penetrates the whale,

expounding down its bones.

He tells of how it came to be

and of it what will come—

sempiternal.

And it is the killings,

his too-pedantic lance,

that stimulate these sermons! that manifest

cetaceous nets,

not wise but merely

otherwisely flawed,

for he himself is seeking

for this whale now to wrest,

to cast claim o’er

& own

what never can be held—

in such Socratic struggle

no gnosis will suffice

and must the whale therefore go

unfathomed.

V.

Often in that autumn, but before it was familiar,

he’d trace the trails of the Haagse Bos

in search of fallen chestnuts.

Fall’s woods were still enfoliate,

caught in the nearby thrum of traffic & peppered

through with pale, broken trunks of birch.

They went together once.

He stumbled on a clutch of conkers and thought

to gather them, but as she pointed out,

they had no bag to carry them, so they went

back to the pale yellow of the midday kitchen, where he swept

coffee nubs & flour as they played etymologies.

“Convergence,” he proposed. “A shared sense

of vertigo” (which was false). She scrubbed

a wooden spoon and set it down to dry

beside the blue Delftware. “To distinguish

is to separate by pricking” (which was true).

Later he read the field guide and she scored

the shells of chestnuts from the market.

The book said Castanea and he was puzzled

by the artifice of even nature. Though it fruits

earlier, the horse-chestnut is not edible,

unlike its sweet faux cousin the sativa—

next time he’d seek shorter leaves

and spines that would antagonize his fingers.

VI.

Having land-

ed, Penn set out the corners of my home

three hundred and sixteen years before I was born

into that stretch of schist and green. The white

-tailed deer that roamed his woods mingled

with the mountain laurel and the upswept oaks.

The soil was dark for all the planting he could do. He would

have wandered as I did in those dense pockets, the maples

in the understory young and lithe, and fattened, too,

his hogs on chestnuts—those keystones whose ribs assured

the split-rail fences and the houses rectitude,

resisting any form of rot. I ate sassafras

and did not stop to think of loss, nor sense

my very casual unknowing (having not yet turned to verse

to know of l’absence in Rilke’s grand & positive intent).

Instead I tripped in nettle by the Schuylkill,

its water coursing toward the city & the port

like in farther north Manhattan where, amidst the bristling,

sylvan smokestacks, a ship bore blight up to our shores

and at the birth of the last century, hurled it over all

the eastern seaboard, cleaving forty million chestnut trees

down to some sparse dozens.

VII.

In the earth hour your myriad self,

your myriad self present and unfolding, du bist.

Your gothic arms, your multitudinous self, loosened

“by the lees of both,” the currents of the air, the whole

eye, bist du. In October the yellowing,

the spined pods dropping to mulch with the orange

beech leaves, du bist und bist,

the lichen & moss

climbing over the greengrey bark and the yellow-beaked

blackbirds turning over leaves in the undergrowth,

du bist, du bӓumst.

Attend, woodnode—the upper sky

is blue the light filtering the green

lichen the blackbirds’ madrigal (du bӓumst, du bist),

looking us into one, unthinking,

du bist, du bist, du bist.

Poet’s Note

The theme of this poem is knowledge & its sundry forms. Specifically, I am concerned with the epistemic gaze, and with the impact of historical and contemporary discourses on knowledge of the natural world. On a literal level, these verses examine chestnuts of three different kinds—the horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum), the European chestnut (Castanea sativa), and the American chestnut (Castanea dentata). The central storyline at work is my own discovery of the natural world: until very recently, I not only had never seen a sweet chestnut tree, but did not know that there was a distinction between the mildly poisonous horse-chestnut (related to the lychee) and the American and European varieties of the sweet chestnut (cousins of the oak and beech). Layered over this unknowing were the historical and cultural problems that contributed to it; for me, like for most residents of “developed” countries, my relationship with nature had grown increasingly abstract, commodified, and, of late, screen-mediated. It took my gradual consideration of various chestnuts—and in particular my horror upon learning of the fungal blight that essentially obliterated the American chestnut in my home state of Pennsylvania—for me to fundamentally reconsider how I thought about, spoke about, and interacted with the natural world.

Each section in the poem represents a different way of knowing, and thus adopts a different discourse, ranging from the most void and without form to far more domineering lexicons. I have tried to speak in various languages, borrowing from Wallace Stevens, Herman Melville, and other fonts of inspiration that seemed appropriate to the mode of thought that I was trying to represent. Finally, central to the resolution of the poem (and its ethic, too) is the German Jewish philosopher Martin Buber’s notion of I-It and I-Thou relationships (the poem’s title is a play on a quote from I and Thou, his most famous book). Buber explains that the I’s merely seeking knowledge objectifies the recipient of its gaze, the It. Only by an unbounded willingness to relate to the Other as Thou, a true coequal, can we step beyond this solipsistic and self-serving conception of the world. This, then, is a poem about hubris and humility, about blindness and sight.

Artist’s Note

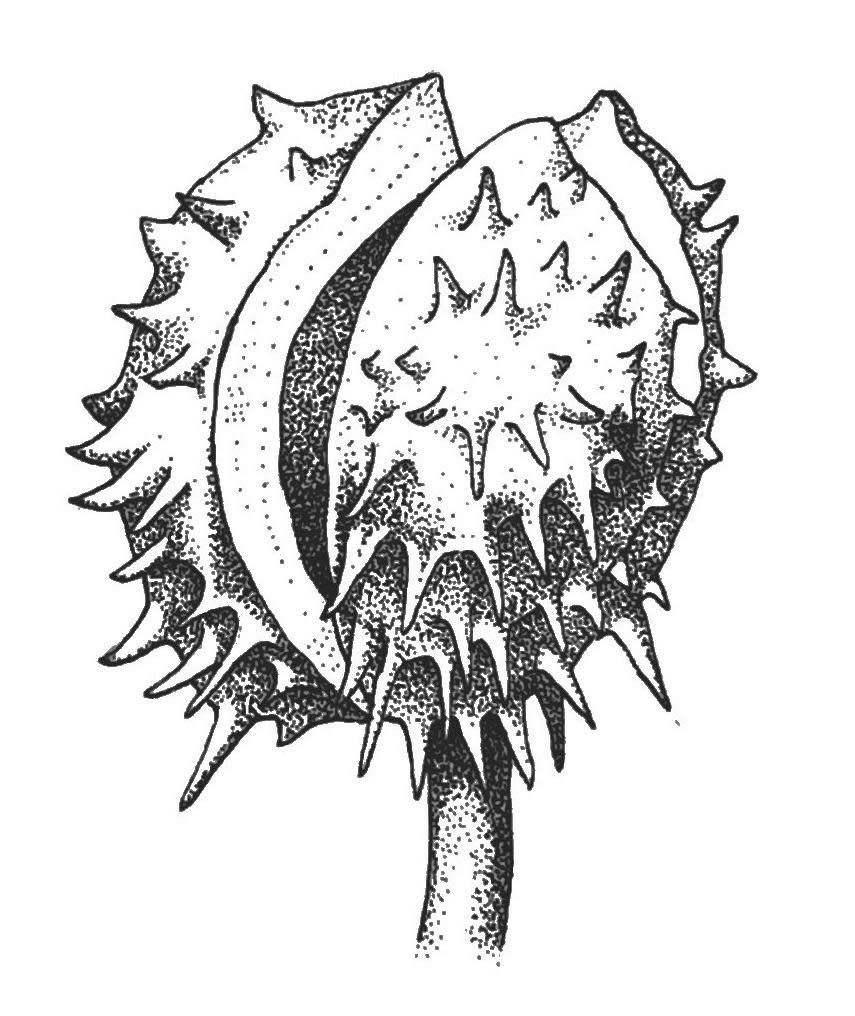

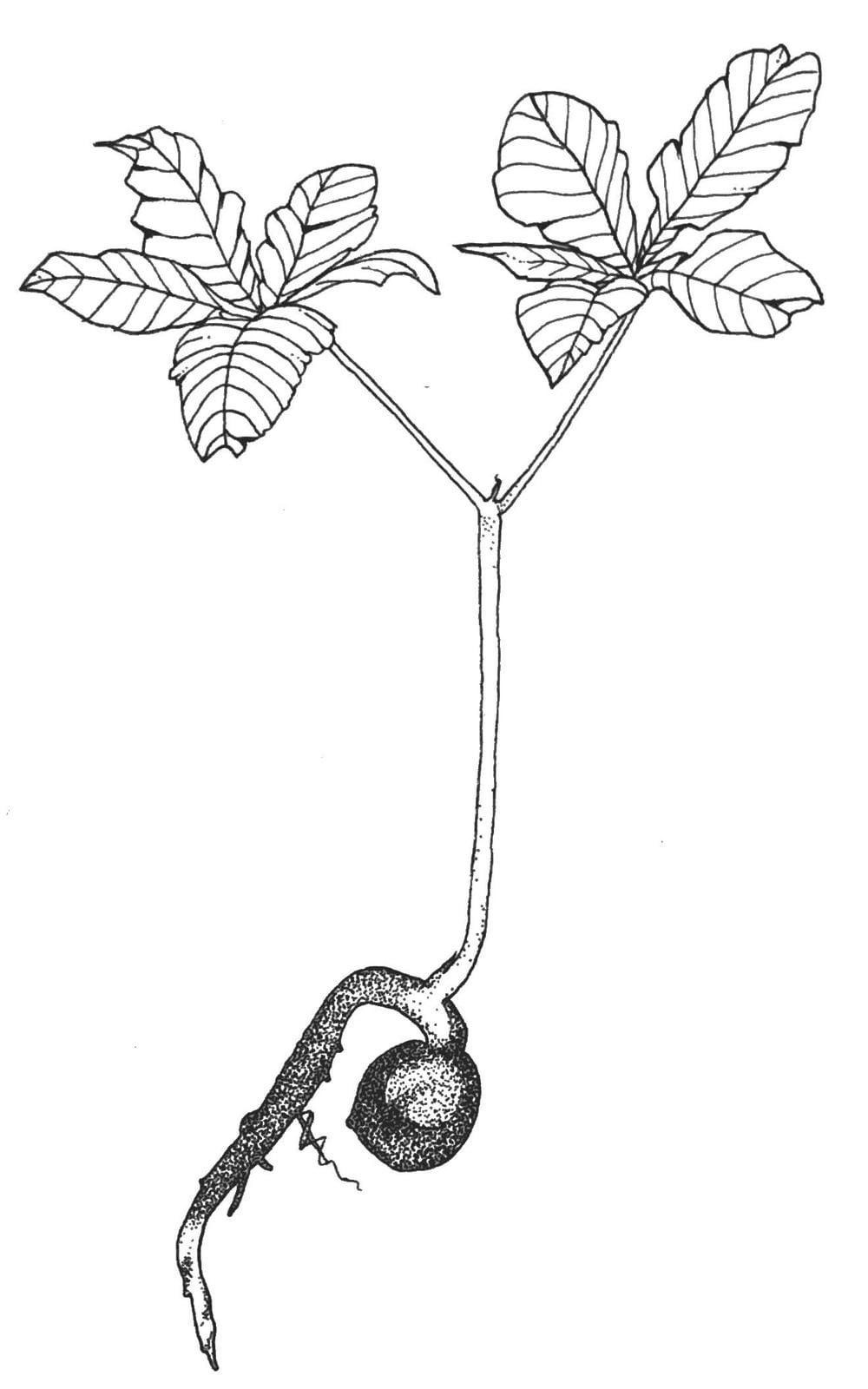

As for the three illustrations, the first two are of Aesculus hippocastanum (image 1 is a horse chestnut seedling whereas image 2 is a seed pod). The third drawing is of Castanea sativa (sweet chestnut seed pod). I used black ink Micron pens on 140 lb. watercolor paper for all three illustrations.

When illustrating “I consider a chestnut”, I chose to employ pointillism within the botanical line drawings. In this way there exists both certainty and uncertainty, both lines and impressions of lines, an image rising or a shadow falling in a tight collection of dots on the page. I invite you to consider the latter half of the first stanza: “Then a chestnut: / impressions of the thing, appearances, dark limbs / against a grey Dutch sky”. Here lies the stark contrast between inky darkness and negative space.