Life is a faint tracing on the surface of mystery. —Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

A ugustine didn’t say this, but somebody did and it is credited to the saint all over the internet: “The world is a book and those who do not travel read only one page.” I don’t know if the traveling part is necessary, I think it’s just the looking. Time turns the pages for us.

What Augustine did say is, of course, more overtly religious. “Our great book is the entire world; What I read as promised in the book of God I read fulfilled in it.” In a later commentary on the Psalms, he urged his followers to “Let the world be a book for you.” We are to read the world as a text. Luther shudders in his grave. The question, as always, is how to see.

I go looking. Some hemlock trees in eastern North American forests have small metal tags nailed into their trunks. The tags identify trees that have been treated for an invasive Asian caterpillar. The caterpillar is a white, fluffy thing that makes its home underneath the hemlock needles. It looks as if it snowed upside-down. The creatures kill the tree, over time. Aldo Leopold said that the penalty of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Tennessee Williams, among others, said that life is one long goodbye.

I am driving through West Virginia. The world is bleak and gray and the leaves are all off the trees. There is a war on in Ukraine. I saw a picture this morning in the news of a family of three that was killed by exploding shrapnel. In the photo, a hand fell out from underneath the tarp. Their bodies lay all crumpled in death at the foot of a World War II memorial. Their sturdy gray rolling suitcase—I have seen the same one on Amazon—was unharmed.

I saw that picture later, on reddit, uncensored. The tarp was gone, and there were three gray people. I recoiled, then looked again. Why does death feel like a violation? I suppose it’s the same reason sex does. Our beginnings and our ends find us at the limit of reason; we are humbled to the point of embarrassment. I am not sure that this is a bad thing. These are the thin places; reverence is required. Here, Annie Dillard says, eternity clips time.

It’s dangerous to venture out beyond the veil, though it hasn’t stopped the mystics, or Moses, who asked to see God’s glory. “You cannot see me and live,” God replied, wrapping up that business a bit too neatly. Well then. What are we to look for? Ezekiel received a vision, but it was mediated threefold—all he could take was “the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the Lord.” Uzzah touched the Ark and died on the spot. Fine. Fear, not love, is the beginning of wisdom.

About the fear of God, Dillard wrote, “I do not find Christians outside of the catacombs sufficiently sensible of conditions. Does anyone have the foggiest idea what sort of power we so blithely invoke? Or, as I suspect, does no one believe a word of it?” In our defense, it is entirely incomprehensible. Belief is just a word. I was force-fed mystery; I swallowed so much that it became a part of me. I think that is the point of the sacraments.

I scrolled down and saw another dead man. He was alone, blasted off of a TV tower by some Russian with a button. He too was gray—his black blood was muted and matted by the dust that collected on his head. I do not want to know who he was.

My mom posted a picture on Instagram today of the Ukrainian flag. “Wake up, America!” She begged. “What kind of world are we leaving for our children and grandchildren?”

I am walking the trail under the cliff and looking for exposed coal seams. I don’t see any, just cracks in the hard rock that time made slowly.

The earth holds all the evidence of our old great wars. Chert blades in Africa and arrowheads in Oklahoma, ancient, rusted muskets in England and Spanish cannons at the bottom of the sea. Over time, the soil takes them back. Slow accumulation of dust and dirt buries our history; a small mercy. The earth knows we can’t hardly bear the ills we see.

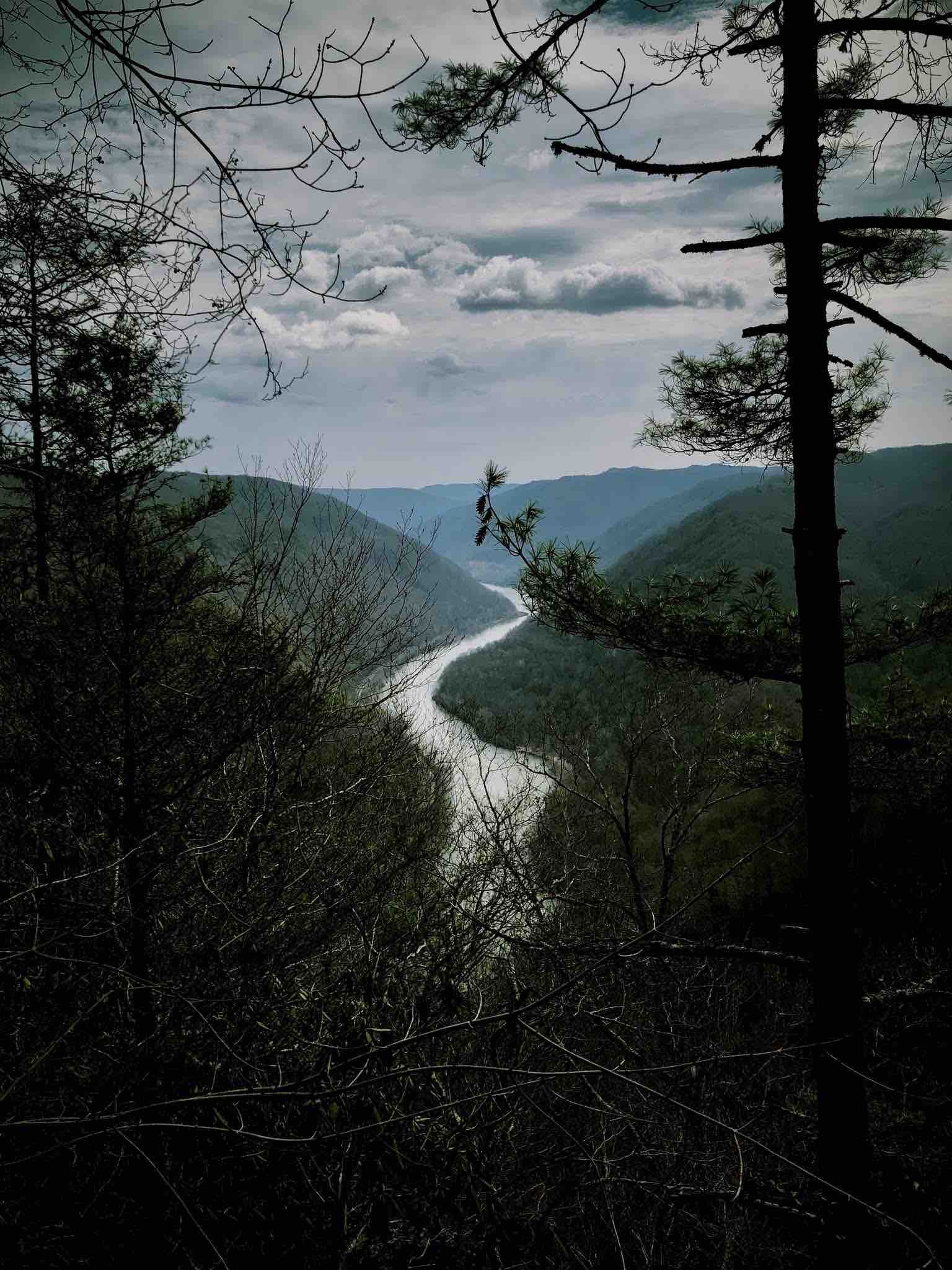

One broken layer of rocks has faint words etched in it. I can make out the first two words—“Who is.” The middle has worn off. The last two words remain— “Our God.” I am not kidding; you can go and see it for yourself. It is on the Castle Rock Trail in New River Gorge National Park. Someone in this ancient rock carved out a Psalm, and time has left the only pertinent question.

In the gospel of Luke, Christ said that if the people are silent, the stones will cry out. Robert MacFarlane wrote that if your mind were only a slightly greener thing, the trees would drown you in meaning. I read the rocks, I listen to the trees, I consider the lilies. The thin places are stretched to breaking. Look: something pours through.

What my mother does know, better than I do, is that you ask for peace from people, not from God. The world we will leave is the world that always has been and always will be. Qoheleth says that there is nothing new under the sun. My professor says that all time is equidistant from Christ. Time, turning its pages, preserves only the essentials. I am not claiming to understand.

I am back on the edge of the canyon. The wind, just buffered by the coal seams under the ridge, now envelops me in its muffled roar. Everything is brown up here. The trees are skeletal, the dead leaves make a bed. It is crisp outside. In some places, the only difference between November and March, fall and spring, is knowing it is so.