W e are all collectors of nothing. Taking pictures of things we’ll likely never spend much time looking at, and never spending enough time on a single object to ever truly experience much of it.

Every kid I grew up with came home with a strangely drawn work of art they’d made which exhibited a new skill, boasting of their newfound talent with a pencil. Having just discovered tracing paper, we all thought we had cracked the secret to make great art. For many, this is the extent of their relationship with this skillset, but for some, tracing finds a way to stay through adulthood. My grandmother and grandfather were two such people who would trace.

Growing up in my grandmother’s house, I often faced strange objects. I was the sixth generation to live in my family’s house, in it there were heirlooms of incredible specificity. My great grandfather’s middle school report cards, century old letters from my grandmother to her sister, my great great great grandmother’s painting of her flowers which still bloom in the yard. Oars from long interred boats owned by my great grandfather hang on a wall and sailing knots tied by his son hang next to them. The lineage of my family is confusing and tangled. The roots in this family home are palpable and intricate even to the most oblivious observer.

On top of the oddities of a more familial nature, my grandparents were collectors of strange looking things themselves. When my grandmother passed away, we found a 40-lb hunk of industrial glass that was once used in the fibreglass factory my grandfather had worked in. We found a pistol which only took hand-forged bullets, and a book of pictures from the 1800s of unknown ancestors, that still to this day, I know nothing about. Knowing my grandparents, they could very easily be someone else’s ancestors but the album was picked up at a yard sale.

Even when faced with objects that had no personal meaning to them, my grandparents were the kind of people who took great pains to preserve the history of their world. Nothing would make my grandmother cringe more than throwing away something she thought should be preserved. “It’s all because she grew up in the great depression,” the adults around me would say. But the older I got, the less I believed that. She was actually just the kind of person for whom objects were the way into one’s soul. I have the impression that this is a family trait and not unique to her. Once the next generation takes on the mantle though, it sure becomes a difficult job to sift through it all.

Although it may seem like we’ve ambled quite far from the topic I teased you with in the start (I fear I may need to jog your memory and remind you that it was about tracing paper), in actuality I think a love for tracing paper is actually an expression of this deeper need to preserve. You see, on the walls of her house, my grandmother had something called grave rubbings.

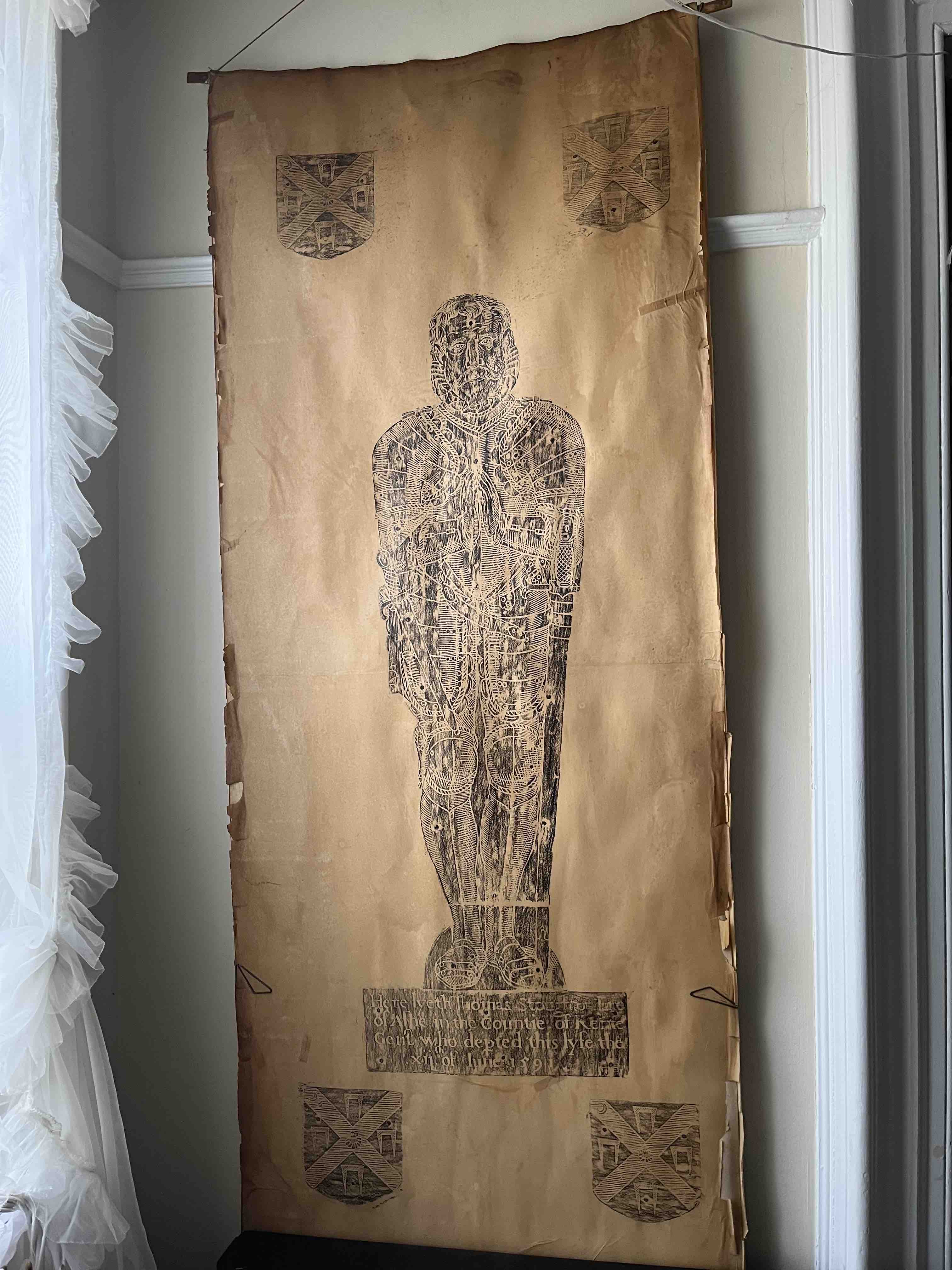

They fell quite steeply out of style in the 20th century with the death of the last Victorians and the advent of photography. Basically, all that’s involved in the practice of grave rubbing is taking tracing paper to a gravestone in order to replicate the art carved into the stone. It was quite popular among religious pilgrims who wanted to take home a piece of a holy site without damaging the reliefs. In my grandmother’s case, we had some grave rubbings of some beautiful carvings of medieval European knights and monks. They are in the photos accompanying this piece.

These tracings are, I think, a perfect representation of the philosophy that created them. They are new and old at the same time. Reincarnation for the soul of an object. Not a facsimile and not purporting to be the same kind of thing, but preserving the heart of the object nonetheless.

I believe we have cheapened something with the proliferation of photos. In the case of grave rubbing, time was taken by a person to lovingly trace the soul of the carving. When we take a picture of the same thing on our phone cameras, it takes barely a second and we are onto the next thing almost immediately.

With the grave rubbing, there is a piece of art that is created in the image of another piece of art. Traced by one hand from the work of another. There is a line. A human line.