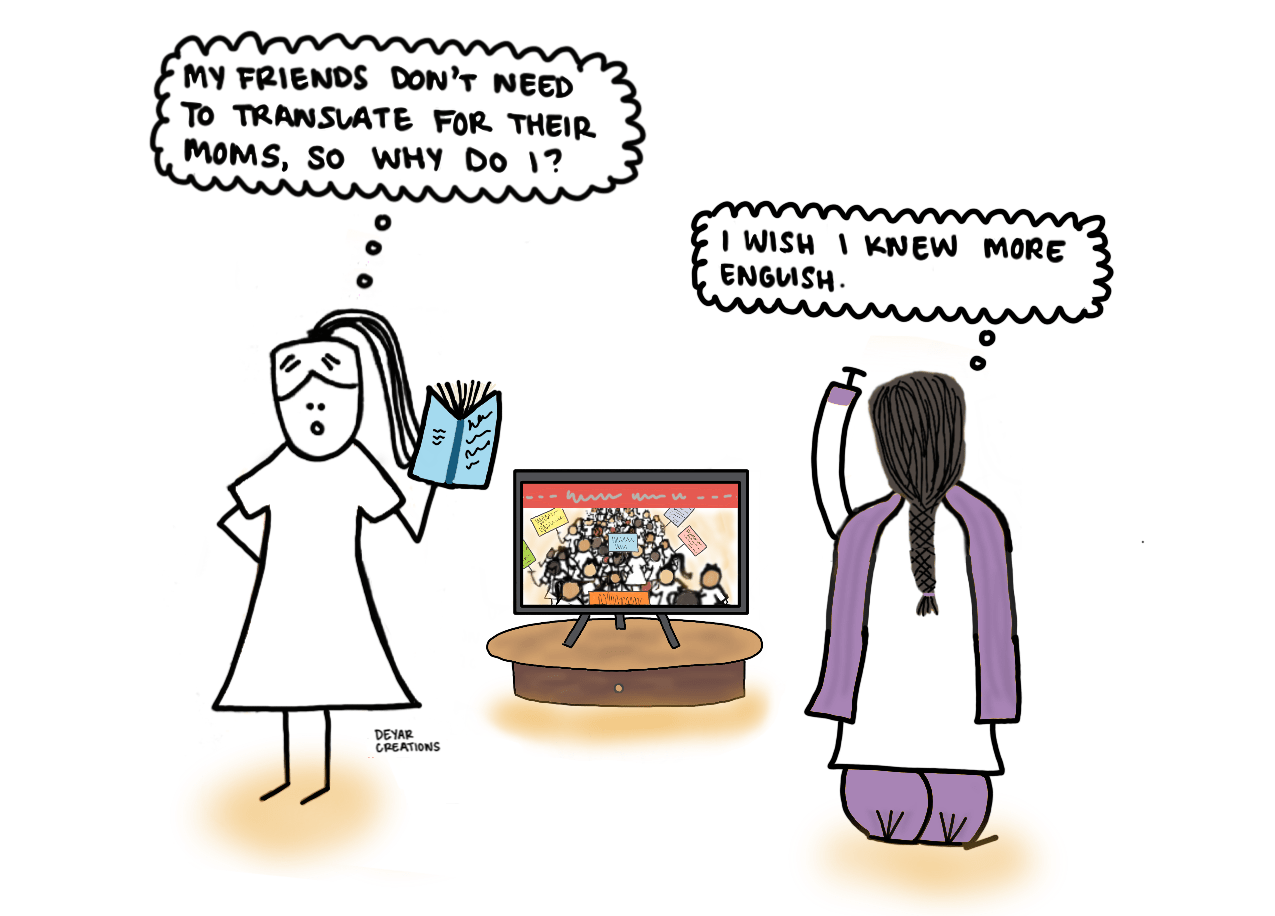

G rowing up as a Bengali American, the most complicated part of my identity was my relationship to language: I used mostly English while my parents were native Bangla speakers. Though I had loved Bangla as a toddler, it became a source of self-loathing as I grew into adolescence. My parents’ foreign conversations drew snickers in public, and my bilingualism was mocked by my classmates. This linguistic experience also posed numerous logistical challenges. As a third grader, I was asked by my parents to explain dialogue in Hollywood movies. By sixth grade, I was editing my parents’ emails, and by eighth grade I was on the phone for them, disputing a fraudulent credit card bill. As my household responsibilities grew heavier, I came to further resent my native tongue.

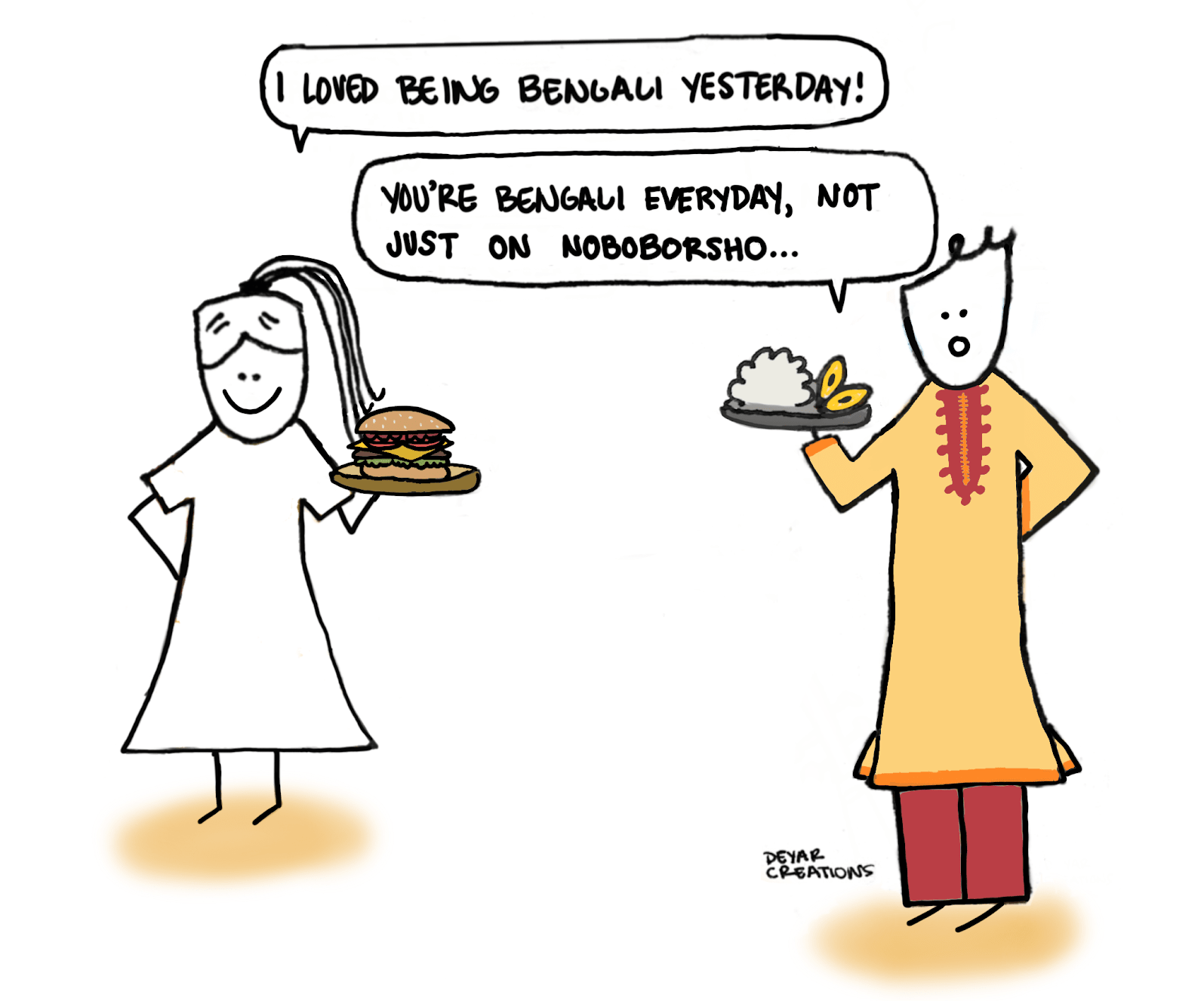

By the end of high school, I hadn’t accepted my linguistic heritage, but instead hoped that it would disappear if I ignored it. I swapped Ma and Baba for “Mom” and “Dad” when speaking to my parents in front of friends. When community members spoke to me in Bangla, I responded in English. I routinely blasted English music in the car, frantically changing the song when a Bangla classic started playing. But when I started college, I became attuned to a strange gap: the absent sound of Bangla. After so many years inattentive—or even unhappy—in my linguistic environment, the hatred I felt for Bangla turned into curiosity. When my parents asked me to come home to celebrate holidays like Noboborsho, the Bengali new year, I agreed. I willingly sat through cultural programs, trying my best to follow along. When the elders asked me about college, I even responded with a few words of Bangla. Once I returned to campus, though, I would never disclose the details of my trips home. I tried to maintain a distinction between the use of Bangla with my family and the use of English with everyone else.

One day in psychology class finally marked a turning point. My professor handed out a quiz called the “privilege self-assessment”. I was familiar with the concept of privilege, but one of the markers of privilege shocked me. “Is the language that you speak at home the same language in which you are receiving your education?” The professor explained that speaking one’s ancestral language is an exercisable right; easy communication with one’s family is a gift; seeing representation of one’s native tongue is paramount for healthy self-esteem. I had never before considered that the frustrations I faced in Bangla were due to my position and that my struggle was common to millions of people across the world dispersed to places where their native tongue is not spoken. This realization kindled my desire to make up for the years I spent rejecting Bangla.

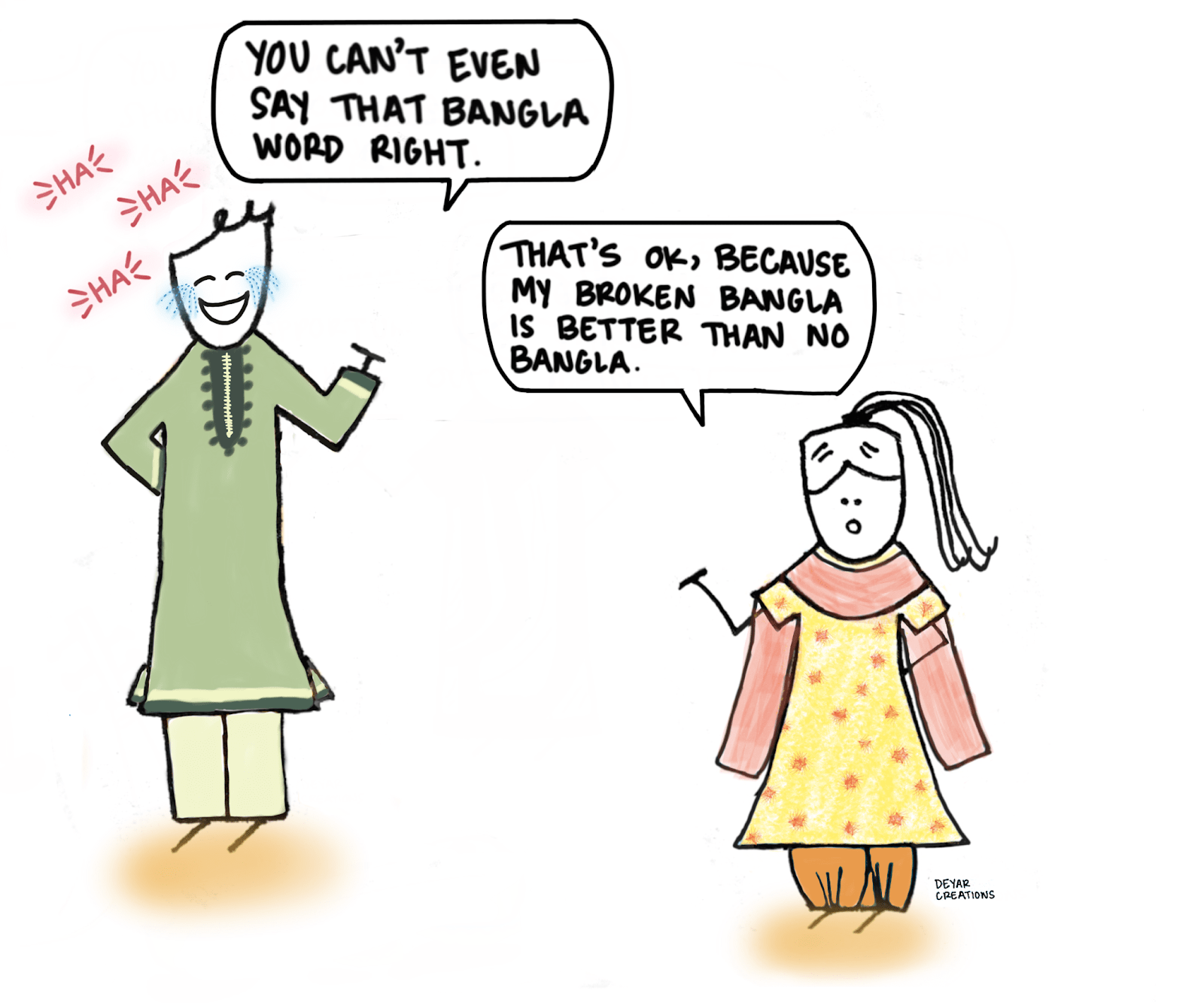

Through the remainder of my college years, I spent every break in Kolkata, India and Dhaka, Bangladesh, where I studied Bangla intensively for months at a time. I obsessively watched Bengali TV, and meticulously practiced my pronunciation in front of a mirror. If my relatives in our homeland could read, speak, and write fluent Bangla with ease, then I would learn to do the same. However, no matter how hard I worked, my eight year old cousin continually pointed out that she could read Bangla much faster. Regardless of my expanding vocabulary, my speaking style still gave me away as a child of the diaspora. Even as my comprehension level increased, I struggled to consistently follow formal conversations or written material. I blamed myself for these defeats, chalking them up to what I saw as my years of rejecting my heritage.

Distressed, I took a break from studying Bangla—but not from thinking about it. I started to make art about my experiences with the language. I created an Instagram account, @deyarcreations, and began to share songs and doodles with captions explaining what I had undergone in the Bengali diaspora. To my surprise, this resonated with a larger audience. As I connected first with other Bengali Americans, then with Bengalis worldwide, and eventually with South Asians from many different diasporic communities, I realized that being a “third-culture kid” was actually a gift. While my Bangla is still not perfect, I am furthering my proficiency and educating others through my work. I have also discovered that keeping my language and culture alive thousands of miles from my motherland is, in a unique and important way, participation in my heritage.