What follows is a conversation between George Gibson, Clifton Hicks, and Symposeum editor Nissim Lebovits. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

G eorge Gibson and Clifton Hicks are saving music. Both are traditional banjo players, two of only a handful of descendants of a particular musical heritage that dates back more than two centuries. As the last cultural institutions that birthed this music fade away, these men have been helping to preserve the story and the place of traditional banjo in American history.

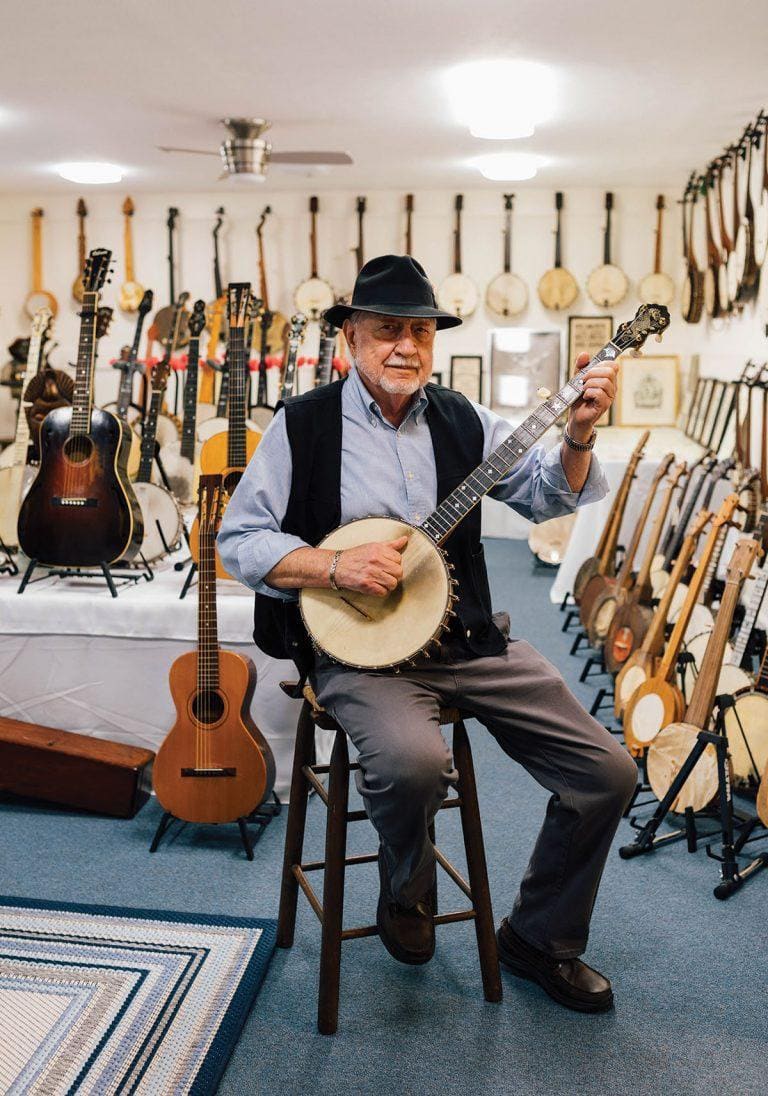

George, a now-retired business executive, has been working for more than fifty years to save the music of eastern Kentucky. In the process, he’s become a key figure in efforts to preserve the history of the banjo. George plays and collects antique banjos, which he uses to record traditional music. He has also published numerous articles on banjo history, and has designed exhibits in various non-profit museums dedicated to the conservation of American folk heritage.

Clifton has taken up the same cause, after beginning to study banjo under George’s tutelage more than twenty years ago. Using digital media platforms like YouTube and Patreon, Clifton passes on George’s lessons, songs, and historical information to thousands of monthly viewers. Together, they form the backbone of a growing online community that is preserving banjo music into the twenty-first century. As the pandemic has made Spotify and live-streamed concerts even more important, and traditional in-person banjo gatherings nigh on impossible, I spoke with them about the banjo, its history, and its future.

Nissim Lebovits (NL): You both grew up in very different times and places. How did you get into banjo playing?

George Gibson (GG): I was born in 1938 in rural Knott County, Kentucky. By the late 1940s the advent of commercialization, radio, and out-migration accelerated by World War II led to the demise of traditional folk activities; community events like dances at school openings and closings, box suppers, quiltings, and bean stringings were no longer held. As traditional music vanished, the many locally composed banjo songs that reflected the area’s history also disappeared. My older sisters told me that our father, Mal Gibson (1900-1996), played banjo and sang for them in the 1930s. By the late 1940s, however, he had ceased playing banjo. This was true for the majority of the traditional musicians in Knott County that did not join the march north. The effects of cultural disintegration led to psychological problems in some, and also to an enormous cultural loss. An internalized awareness of this loss was one of the reasons that I eventually tried to save songs that reflected the history of the area, and although I managed to save some, many were lost.

By the time I began playing banjo around 1950, most aspiring banjoists had switched to learning the style of three-finger picking pioneered by Earl Scruggs, who in the 1940s popularized what came to be called “bluegrass.” However, I had a neighbor, James Slone, who still played traditional banjo. There was no formal method of teaching banjo in the rural South, so I learned banjo as Southern musicians always had: by emulation. I listened to Slone’s playing, watched what he did, and tried to reproduce the sounds his banjo made. By doing this I ended up with my own style, which is not a copy of Slone’s playing. Most people today learn by imitation from teachers or tablature in books or magazines. This has led to the spread of the standardized style popular today, known as “round peak,” and to a loss of diversity in Southern playing styles, which were never homogenized in any way.

After learning to play banjo I persuaded a few neighbors to play and sing for me. However, I noted they could rarely remember all the verses to their songs. This led me to search for lost verses, particularly for the songs that were local to the area, for they were a part of the history of the area. I pieced a few songs together with verses from different sources, one song of this type was “Old Smokey.” I got a few verses from my mother and some from John Hall, who sang a verse or two for me. I then selected a banjo tuning I thought fitted the melody and played and sang the song for them; both said the song I performed was close to what they had heard previously.

After college I taught school locally before leaving Kentucky for better opportunities in the north. After leaving teaching I became an executive at a Fortune 500 company in Philadelphia, but resigned after thirteen years to pursue business interests in Florida. During this time, however, I spent as much time as I could in Knott County engaging with people who had knowledge of our vanishing folk culture.

Clifton Hicks (CH): My earliest musical experience came from an old man who sold watermelons out of a wheelbarrow. He lived around the corner, near a full-service gas station where he bought ice. Every summer he paced up and down the streets and alleys connecting the neighborhoods, singing at the top of his lungs a simple song about his produce:

Ice cold watermelon

Coldest watermelon

In Georgia

When I was thirteen, my father paid a hundred dollars for a second-hand banjo at Bill's Music Shop & Picking Parlor in West Columbia, South Carolina. He also bought three metal fingerpicks and a “bluegrass banjo” instruction manual. We both tried to play it, but after a few months we lost interest. At the end of the summer I carried the banjo to my mother’s new home in Florida, where I was enrolled in middle school.

Later that year, I happened to meet a man named Ernie Williams, who was something of a local folk personality. Ernie taught me how to play the banjo using the ball of my thumb and the back of my forefinger—a style he’d learned from an older man in Sand Mountain, Alabama, who called it “rapping the banjo.” Ernie was the first person I ever saw who sang with the banjo, and he encouraged me to sing with mine.

The next year, my mother came home with a cassette tape album titled Last Possum Up the Tree by George Gibson. I had never, and have never, heard anything like it. Like Ernie, George could sing and play the “rapping” style, but he also fingerpicked beautifully, sometimes with two fingers, sometimes with three. And sometimes, he made sounds so remarkable that my ears couldn’t comprehend how he’d made them. In those days, George had his mailing address printed on the back of the liner notes, so I wrote him a letter introducing myself and requesting an in-person meeting. He accepted.

GG: Clifton was already a good banjo player when he began coming to see me in Florida, and is now a better banjo player than I am. I emphasized that he ought to learn the songs and techniques, but develop his own style. I believe he is now using this approach when teaching banjo.

NL: So much of American folk music is a synecdoche for American history. The banjo in particular is wrapped up in this. Could you tell us a bit about its history?

GG: The banjo was brought to North America by enslaved Africans who were carried across the Atlantic against their will. During the 1700s, it became a part of white folk culture in colonial east Virginia and Maryland where slaves and white indentured servants socialized together, resulting in unions between free Blacks and white female indentured servants. The descendants of these families moved south and west on the early frontier as racial hierarchies were increasingly codified and enforced by colonial governments. In the process, they spread their creolized culture—including the banjo—to their neighbors.

Northern blackface minstrelsy, which began in the 1840s, is popularly believed to be responsible for planting the banjo in white southern folk culture. White minstrel entertainers blacked their faces and played the banjo on stage while stereotyping, parodying, and intentionally demeaning African Americans. These grotesque acts were the beginning of musical theater in America. It is assumed the banjo was brought south by soldiers returning from the Civil War, where they are presumed to have seen the instrument for the first time, or by northern blackface entertainers after the War. Those who support this argument do so by citing the well documented history of the banjo in minstrelsy and not by citing southern folklorists or historians, which would be inconvenient. In fact, as I proved in my essay in the book Banjo Roots and Branches, the banjo was widespread in white folk culture before the Civil War, from the Carolinas to Arkansas, and in Kentucky, from the western flatlands to the Appalachian mountains.

Finally, it’s worth noting that the term “folk music” is confusing at best. I prefer using “traditional music” or “traditional banjo” to separate the older music in the South from the term “folk music.” Prior to the 1930s, folk music meant the in-home music of ordinary people, as opposed to commercial or art music. The early in-home banjo use in the South consisted of traditional music learned from various sources and played for family, friends, and neighbors. When the folk revival began in the 1930s, however, this definition became amorphous; it came to include the music of people in the 1940s and later who sang commercialized versions of folk songs. Today, “folk music” has grown even more imprecise—it now includes the music of people who write their own songs and perform commercially. The use of the term today is therefore typically ambiguous and often inaccurate.

NL: How was it that popular perception of the banjo’s history came to be so different from the instrument’s actual social history?

GG: The banjo remained nearly invisible, restricted to southern Black and white folk cultures, until the 1840s. During this time, white southern musicians Joel Walker Sweeney and Archibald Ferguson introduced the instrument to the burgeoning minstrelsy culture, which was concentrated in the north. Claims that minstrel entertainers learned their music directly from slaves was a marketing ploy meant to lend credence to their acts. However, these claims helped spread the false notion that the banjo was exclusively a slave instrument before the 1840s.

The reason many embraced the minstrel origin is the lack of contemporaneous citations of the banjo in white southern folklife before 1840s minstrelsy. Folklorists know, however, that people do not comment contemporaneously regarding folk activities common in the home. A good example is the southern ballad tradition that was “discovered” by ladies at the Hindman Settlement School in Knott County, Kentucky, in 1902. Students boarding from outlying areas of the county brought their in-home banjo playing and ballad singing to the school. Although there are practically no contemporaneous citations of southern ballad singing in the home prior to the 1840s, no one doubts that this tradition was brought to Kentucky by pioneers from Virginia and Maryland. The origin of the traditional banjo, however, has been erased.

Looming in the background is the hillbilly stereotype, which is so pervasive that most do not realize that it influences their thinking about southern mountaineers. A few urban revivalists, who fell in love with traditional banjo, decided that mountaineers could not have possibly created the music they liked. It was convenient to say that the mountaineers were taught not by African Americans, but by northern minstrels strutting in blackface while imitating African Americans. So certain were they of this that none did any extensive historical research into the social history of early America.

“As traditional music vanished, the many locally composed banjo songs that reflected the area’s history also disappeared.”

Those who lack Appalachian roots—and even some who don’t—fail to recognize the harm the hillbilly stereotype has inflicted, and continues to inflict, on Appalachia and its residents. Oil, gas, and coal companies have relied on the hillbilly stereotype, which is ubiquitous in American popular culture, to conceal the extent of their environmental destruction. This stereotype is responsible for many people believing that the people of Appalachia are themselves responsible for the many problems they face, including health issues, decreased longevity, and a blighted environment. To this day, people outside Appalachia are amazed when I tell them that gas well fracking and coal mining have destroyed over 80% of the water table in east Kentucky. How does one explain this? The best answer is the hillbilly stereotype, which is the band-aid that covers the sores of Appalachia, and lives on in media, in popular movies, plays, and books.

Having grown up in a southern folk culture that included the banjo, I recognized that the minstrel origin of the southern folk banjo was both counterintuitive and improbable. I began researching the banjo’s history by consulting historians, folklorists, and oral history as well as original sources in journals, newspapers, and magazines. I found citations of the banjo in white southern folklife prior to the 1840s. However, most are not contemporaneous; they are from people nostalgically recalling their youth, or repeating what their grandparents recalled about their youth.

CH: I’ll add that anyone who learns from me must come away with the understanding that the past two centuries of banjo history are characterized by a vast, indescribable, dazzling array of styles and customs. What exists today is only a remnant of a culture which has survived countless near-extinctions, each destructive event creating a narrow bottleneck through which only a fraction of the tradition has passed.

NL: Speaking of popular banjo perceptions, where do associations with bluegrass and “hillbilly” stereotypes come from?

GG: In the first half of the twentieth century, southern folk traditions underwent dramatic changes. Banjo playing by both Black and white musicians became increasingly professionalized in venues like minstrel shows and vaudeville. The use of the banjo for home entertainment declined as a result. Square dances, which featured the banjo prominently, lingered in the mountains but disappeared in areas where commercialization brought new instruments and dances. This fostered the idea that the banjo was a “mountain” instrument.

Ultimately, it was radio that helped preserve the banjo in the south. Traditional music still existed in some areas of the south when radio stations found that string band music featuring the fiddle and banjo was popular with their listeners, Black and white. Shows like the Grand Ole Opry, a Nashville radio station formed in 1925, helped promote this style of music. At the same time, however, stereotypes promoted by writers like John Fox, Jr. helped cast the banjo as a “hillbilly” instrument. Then, in the 1940s, Earl Scruggs brought radical change to the southern banjo: he introduced a new style employing steel finger picks and a unique three-finger approach. This style became known as “bluegrass,” and by the 1970s was the dominant banjo technique, isolating the remaining southern banjoists who still played in traditional styles. Today, bluegrass music is the sound most associated with the banjo in popular culture.

Meanwhile, in the north, an urban banjo revival had begun in two waves, first in the 1940s and then again in the 1960s. The first phase stemmed from a broader folk revival beginning in the 1930s, while the second coincided with the counterculture revolution of the Vietnam era. Like northern minstrels, however, urban revivalists adopted an instrument foreign to their culture. As a result, they created a homogenized banjo culture disconnected from the instrument’s southern roots. Their style became the dominant style taught through books and magazines, and now the internet. While remnants of older southern banjo traditions linger in some mountain areas of the south, most people who learn banjo today do so in the culture created by the urban banjo revival.

NL: Folk music has long been tied up in American popular memory and protest, not just during Vietnam, but also in westward expansion, the Civil War, Jim Crow, and so on. Clifton, you’ve talked before about being a conscientious objector. Is that in any way connected to the music that you play?

CH: Most people experience some kind of violence in their lives. My own life has, at times, been exceptionally violent. My youth was spent fighting, so when I became a “man,” it seemed practical to make violence my profession. With my family’s consent I enlisted at the age of seventeen in the U.S. Army. I carried my banjo, and George’s songs with it, through the battlefields around Baghdad where I served in an armored cavalry squadron during the early years of the Iraq War. It was here that I first played songs like “Darling Cora” and “Old German War” for strangers, and soon these songs (especially “German War”) became favorites of the men and boys I fought alongside. Every night, whenever the situation permitted, I would lay my rifle down and pick up the banjo, and a small group would assemble to hear the songs I’d inherited from George.

I’ve been across that great ocean and I’ve rode down the streets of Hell

I’ve lived a life of misery and I’ve been where Death he roams

I’ll tell you from experience boys, you had better stay at home.

Although I was a member of an armored cavalry squadron, trained and equipped with high-tech weaponry, most of the violence that we inflicted was accomplished without firing a shot. We beat people with clubs, kicked and stomped on them, struck them with our rifle muzzles, and sometimes crushed their bodies with our vehicles. Many times I was shot at; many times I dove into the earth as mortar and rocket shells burst around me; but only once did I ever fire my rifle directly into someone. When I did, the man collapsed out of sight. I have no idea what became of him.

On a U.S. Army base in Germany, between deployments and away from the battlefield, we found ourselves suddenly with ample opportunities to reflect on what we had experienced. It wasn't until I'd been in Germany for a few months that I realized the gravity of what had taken place, and of what I would be expected to do on the next deployment, which was imminent. I came to the realization that the pain and terror I’d inflicted during the course of my life had, in most cases, been unjust. That realization became the impetus behind my transition from the life of a professional killer to that of a conscientious objector.

These events affected my relationship with music in ways that are not easily described. Whereas before, as a youth, I took great pleasure in singing violent murder ballads like “Frankie & Albert,” “Pretty Polly,” “Stagolee,” or “Wild Bill Jones”—reveling in the recitation of each bloody verse—I now find lyrics like these less attractive:

And the heart's blood did flow,

And down in the grave

Pretty Polly did go.”

“Stagolee shot Billy

He shot him with his forty-four,

Billy fell back from the table

Crying, ‘Stag, don’t shoot me no more.’”

While these songs are still of great interest and value to me from a cultural and historical perspective, the act of singing them has become something of a burden, and I only do so when asked by a friend or a student of mine. It requires me to purposefully detach myself from some of the lyrics, no longer daring, as I did in my youth, to welcome the gruesome imagery into my mind. In that sense, I don't know many people who would be able to sing these songs with my level of conviction—where these images had once been artificially projected by my childish imagination, they are now conjured up from bitter memory.

I survived the war, became a conscientious objector, and was honorably discharged from the U.S. Army on December 26th, 2005. A number of my friends did not survive.

In November of 2018, George asked me to play “German War” for him. I did, and I have not played it since.

GG: The “Old German War” is a song unique to Knott County, Kentucky, which had many volunteers in World War I. My father had a close friend, Jonah, who served overseas. After the War, my father’s friend became alcohol dependent; although he raised a large family, he was often drunk. He did not share his war experiences with his family or friends. However, I accidentally learned what haunted him when visiting his home.

“[T]he digital, online medium—though deeply anachronistic in the context of traditional banjo—may, in the right hands, be used to create something approaching an authentic experience.”

Jonah was drinking with a friend and both were inebriated. Jonah was holding his reading glasses in his hand when he became agitated. He beat his glasses on the arm of his chair and said to no one in particular: “He had his arms up, he said ‘comrade, comrade,’ he wanted to surrender, but I shot him, I shot him, he was just a boy.” The Germans had boys as young as fifteen serving before the war ended. Jonah had evidently shot one of these boys in the heat of battle; this haunted him for the rest of his life. At sixteen, Jonah entered the army, only a boy himself. Although he’d been a banjo player, he likely didn’t write the “Old German War” song. I believe it was his neighbor, Mel Amburgey, who also served in the First World War. I also knew veterans of World War Two who had demons; one was a banjo-playing cousin of mine who eventually died of his war wounds. For many people, war never ends. Unfortunately, we continue to elect leaders, with disastrous results, who are oblivious to this.

NL: It seems a bit paradoxical to have a digital forum for folk music. It’s a genre that tends to be best experienced live and in-person, right? How have new technologies changed that, and what role have they played in disseminating folk music?

GG: Musicians have always managed to take advantage of new technology. My father told me he played over the telephone with a fiddler for neighbors on Little Carr Creek in 1916. I initially doubted this because I didn’t think we could have had telephones in 1916, since I didn’t see a telephone in our home until the 1950s. I had seen remnants of old telephone lines in the area when I was a boy. However, these lines were abandoned sometime in the early 1930s as the Depression deepened. I once found a book of poetry by William Aspenwall Bradley, entitled Singing Carr, in which he described walking to Carr Creek in 1916 and seeing residents of a log home listening to hymns sung over the telephone. Bradley named his book “Singing” Carr because of the number of traditional singers he found there.

CH: The idea of staged banjo performance—ascending the stage, peering down at a ticket-holding audience, and singing through a microphone—is counter to the banjo songster tradition. On the other hand, the digital, online medium—though deeply anachronistic in the context of traditional banjo—may, in the right hands, be used to create something approaching an authentic experience. As songsters, we can film our performances in a traditional setting (such as the outdoors, a barn, or the fireside), upload it, and plainly present it to the eyes and ears of the observer. More often than not, our audience is at home—the place where traditional music has always been performed—and more and more often, viewers are visiting digital platforms to learn the tradition, not merely to enjoy it as entertainment. Digital platforms also welcome a broader audience: like festival goers, my viewers often hail from urban centers (various cities in California, Texas, and Ohio currently top the list), and the majority are scattered across North America, Europe, and Australia.

NL: Clifton, speaking of technology helping disseminate folk music, your banjo heritage project brings banjo history and technique to viewers online. Can you tell us more about how this project got started?

CH: My long-term learning/teaching project, which doesn't really have a name but may be referred to as Banjo Heritage, began in the former Wehrmacht barracks I lived in as a twenty-year-old soldier outside of Büdingen, Germany in 2005. I purchased a refurbished laptop computer and a cheap microphone, and I began recording all of the songs I'd learned from George. My squadron was preparing to return to Iraq, and I was concerned that I might be killed without leaving any trace of this musical inheritance. By 2007, I was out of the army, and recording segued into filming. I began by filming other musicians, especially after 2008 when I moved to Boone, North Carolina, and immersed myself in the remnants of that area's “old-time” folk music scene.

When my mother killed herself in 2012, a few months shy of my college graduation day, I entered into something of a musical hiatus. The morning I learned of her death I walked straight home from campus, took her old guitar off the wall, and played “Will the Circle Be Unbroken”:

Undertaker please drive slow,

For that body you are hauling

Lord I hate to see her go

I hung the guitar back up in its place, and I didn't touch it, or a banjo, again for many months. In 2014 I met my wife, and with her encouragement began to play and sing more frequently. In 2018 I launched the Banjo Heritage project in earnest, and have been filming and sharing music, music lessons, and historical information relevant to banjo culture ever since, mostly through YouTube. The stated goal of this project is to spread the musical and cultural inheritance that I have received mostly from George, but also from Ernie Williams and others. I will continue to share this heritage with as many people as I can, until I am physically prevented from doing so.

NL: George, it seems like Clifton’s approach to this musical heritage has mostly focused on its propagation online. Can you elaborate on your approach?

GG: In an interview for the Winter 2017 issue of Western Folklore, I laid out the idea of “cultural strip-mining,” regarding the extraction of southern music for commercial purposes. Cultural strip-mining occurs when people from outside a culture distort its history and appropriate its music for commercial purposes without properly attributing that music to its source. A good example is a performance I heard on the stage at the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival in Asheville, North Carolina. A well-known academic, who moved south during the countercultural revolution of the Vietnam era, performed a banjo song on stage, word for word, that was unique to an extraordinary Kentucky banjo songster, Rufus Crisp. He did not mention Rufus Crisp or the source from which he acquired this song. A few in the audience may have known where this song originated, but most would not. I let him know that I thought this was inappropriate. Also inappropriate is claiming a connection to southern music by exploiting the hillbilly stereotype, such as naming your band “moonshine holler.” Some musicians, however, have used elements of traditional southern music to create their own music. I admire musicians, such as Gillian Welch and David Rawlings, who have done this.

“Our tradition does not exist on paper, nor on the stage, nor in the classroom.”

Back in the 1960s, which was the peak of the American folk revival based in Greenwich Village, one of my sister’s friends owned a publishing company in New York. When she learned I played banjo, she saw an opportunity to discover another folk star, or at least make some money from publishing new music. She insisted that I audition for her. I did not want to, but I had no easy way to escape. I felt protective of the little music I had, and thought it had limited relevance to the folksongs and folksingers of the day. When I auditioned, I sang in the worst possible manner and mangled the banjo accompaniment. After this, she never mentioned my banjo playing again.

NL: What do you think of the work you see from other banjo players and musicians interested in banjo heritage?

CH: Most other musicians have learned their craft from tablature books and university music courses. Those who’ve taught them (often in formal, paid settings) learned from the same inauthentic sources. Furthermore, these musicians tend to associate exclusively with others who regurgitate the same music, and the baseless dogma which accompanies it. Consequently, their music bears little resemblance to the actual tradition.

For my own part, I rejected tablature and formal music lessons from an early age. Instead, I sought out flesh-and-blood tradition-bearers such as George Gibson. When I couldn’t find people like George, I found others who, like me, sought the tradition at its source, and I learned from them. This process follows the archaic tradition by which banjo songsters, for more than two hundred years, have passed their secrets between one-another. Our tradition does not exist on paper, nor on the stage, nor in the classroom.

Of all the younger people who have learned George's music, none have attempted to copy his style. Although we’re all certainly influenced by him—and by many other traditional banjo players, too—none of us would ever try to imitate his playing note for note. This value is one that George has actively hammered into all of his students’ minds since we first encountered him, and it's a value that I think was harshly instilled in him from his earliest years. In all of my dealings, either privately with students or with the public, I have endeavored to make that value central to the experience.

NL: After all these years of history, what is the future of traditional banjo music in the twenty-first century?

GG: Traditional music, which is meant to be shared with friends and family, will change in the twenty-first century, as it always does. The traditional music I knew as a boy is now splintered. The culture that supported it collapsed long ago. Some of this music is lost forever, but some of it is being preserved and distributed digitally like what Clifton does. Furthermore, some community groups in the South have created organizations to teach young people to play traditional music. The success of these efforts leads me to believe that some portion of traditional music will survive well into the twenty-first century.

CH: As of this writing, many of us are living under the burden of government- and socially-mandated lockdowns in response to COVID-19. Where I live, in rural Georgia, little has changed. Daily life for my family and most of my neighbors continues much as it did before the pandemic. I’m still free to express my culture by carrying the banjo and a few cans of beer to visit a neighbor. That being said, I am aware that many of my online banjo students live in densely-populated urban and suburban areas. People in these places are suffering in new ways, and many are seeking new ways to connect with culture. Of the thousands of people who view my banjo performances and instructional material, many hundreds live outside of the United States. This is proof not only of the banjo's internationalist character and its unlimited value as a human artifact, but also of our natural human desire to know and to belong.

On the one hand, I feel no obligation as a conduit of this heritage. I see myself as one of the millions of banjoists who will live, die, and ultimately amount to very little. If during my brief life I have musically conveyed one genuine emotion, or passed on one endangered folkway, then I will have done more than was expected. On the other hand, it's easy to saddle oneself with weighty obligations to ideas of culture, family, ancestors, young people, the truth, and so on. The old music, and the old instruments themselves (especially the homemade examples) are a window into the essence of what it means to be human across time and space. Having inherited the knowledge and ability required to open such a window, I find myself deeply obligated to in some way maintain it, so that it may remain open after I am dead. ◘